The Data Act: preserving privacy and putting citizens in control

In recent years, we have seen an explosion in the development of “smart” and “connected” devices: from home appliances to industrial machines, and medical equipment to cars. The EU wants to make better use of this data to benefit the economy. I have been negotiating on behalf of Renew in the JURI committee, to make sure the Data Economy is fair, doesn’t harm businesses, puts citizens in control of their data, and prevents abuse of data, be it by governments or companies.

On Tuesday 24 January, the JURI committee voted on our opinion on the data act after months of tough negotiations. In our opinion, we proposed lots of changes that would improve the lives of citizens across the Union, protecting privacy and consumer rights. Lets jump in!

Reacting to public emergencies

When the COVID pandemic struck in 2020, member states were desperately trying to get data that would help them predict the location of the next cluster: data from mobile phones, sewerage plants, and roads were used, and helped governments respond better to the pandemic. But this sharing was entirely voluntary, and made lots of people ask about the impact on privacy and fundamental rights. That is why the Data Act has a chapter that sets out how public authorities can ask companies for data in emergencies.

But their proposal doesn’t provide enough protection from abuse by governments: governments could declare an emergency and force companies to hand over personal data on citizens, with only “best efforts” to keep your identity secret. For me, it was important to strike a proper balance: this tool wasn’t supposed to be used to snoop on citizens, but rather to give public authorities general data to solve crises.

This is why, on behalf of the Renew group, I put forward amendments to address these issues. At the end of tough negotiations, we finally agreed that if a public body wants to request personal data, they have to justify why non-personal data isn’t enough, and in any case, the data must be anonymised, and public authorities are not allowed to reverse that anonymisation.

I believe this gives governments the tools they need to address crises without giving them more powers to snoop on our private lives.

Protecting businesses while sharing more data

One of the key concerns of both companies and non-governmental organisations on this file was trade secrets: product manufacturers were convinced that the Data Act would force them to share their trade secrets with everyone, and NGOs were concerned that manufacturers would label data as a trade secret to avoid sharing.

For that reason, in JURI, we worked hard to find a compromise that empowers both users and manufacturers, giving product users the right to access data, and manufacturers the right to set out the conditions of access, for instance what security measures must be taken to protect the data. Finally, in case of abuse, we gave manufacturers the possibility to suspend sharing, and set up a process for resolving conflicts.

Putting citizens in control of their data

With more and more connected devices in our homes, we believe citizens need to remain in control of the data generated by devices, and of the data they share. Unfortunately, that hasn’t been the case so far: Smart fridges that will automatically order groceries, but are locked to a single supermarket, smart appliances that only work with one home assistant, heating and cooling systems that won’t turn on because a server somewhere in the world has been switched off, and insecure smart bulbs that leave you frequently in the dark.

All of these issues come down to the way your smart devices share data, and instructions with remote services. The data act wants to give citizens back control, giving them more control over data sent to the manufacturer, as well as the right to access and share their data with third party services in a way that is usable.

Finally, we also fought for a right to use devices anonymously, as well as a prohibition of profiling of individuals using their smart devices, because when you buy an appliance, you shouldn’t be the product!

Protecting consumers in the era of the Internet of Things

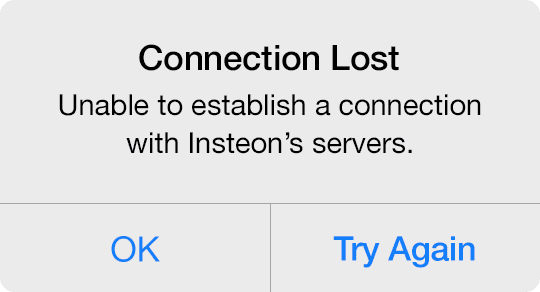

Finally, consumers have experiences issues with “connected” and “smart” devices that rely on remote services: for instance, in 2022, major smart device manufacturer Insteon shut down their servers, essentially rendering all the smart devices they had sold useless, and they are not the only ones: we are also seeing manufacturers discontinue a specific model of a product and shut down associated services, forcing consumers to upgrade, and creating e-Waste.

We want to clamp down on these practices by forcing manufacturers to guarantee a minimal lifetime for services, and to put that information on the packaging, but we also want to empower consumers to pick devices that don’t rely on manufacturers’ cloud services, by also putting that on the packaging. Finally, we guaranteed the right of citizens to tinker with products to keep them working or provide aftermarket services for them: just because the manufacturer doesn’t want to support your device, it shouldn’t mean you can’t use it anymore!

What happens next?

Our proposals have cleared the first hurdle: they are now the official position of the JURI committee. But there is lots more to do in the lead committee where the final decision will be made. I have already reached out to my colleagues in ITRE to ensure that our proposals are taken into account, and I will keep fighting for better, fairer, greener smart devices, and citizen control over their data!